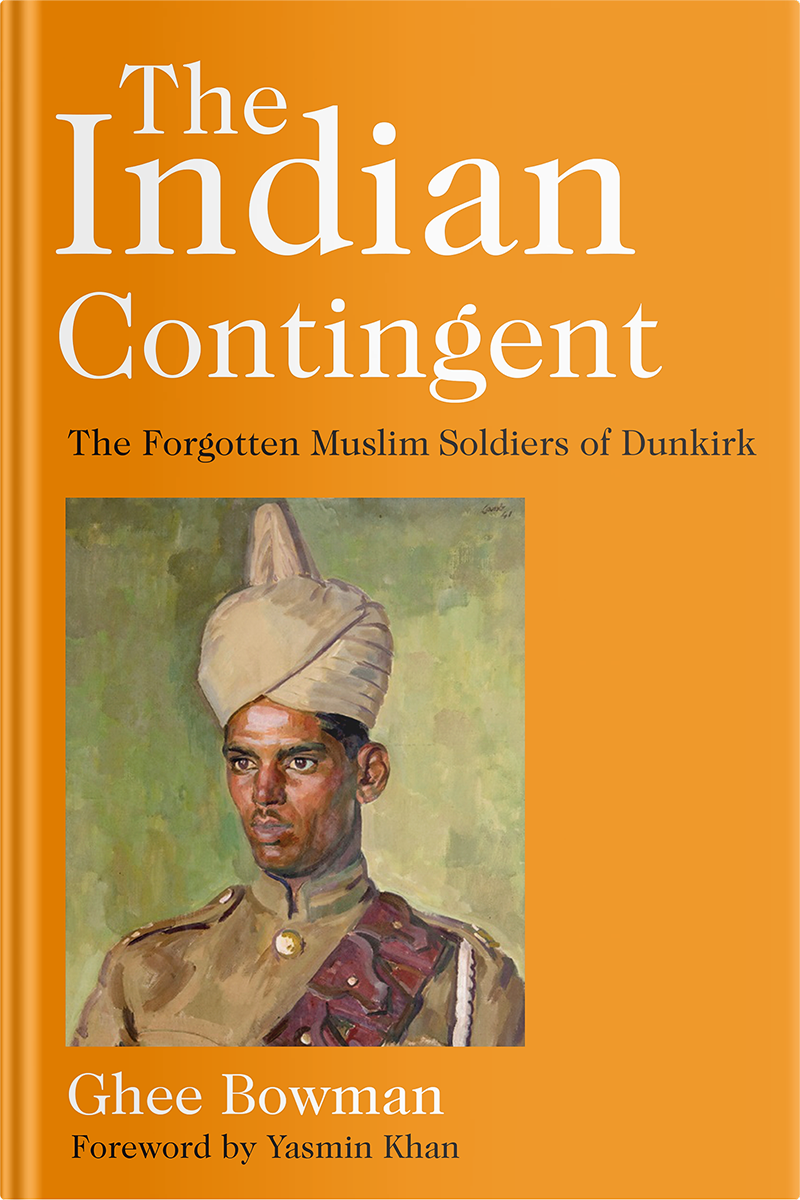

Mohamed Ashraf Khan was the Risaldar-Major of Force K6 when they arrived in France in December 1939, and continued in that role through most of their time in Europe.

The rank of Risaldar-Major was similar to a Regimental Sergeant Major in a cavalry regiment. He was the senior Viceroy’s Commissioned Officer (VCO) in the force, responsible for discipline, for communication between white British and Indian troops, and for keeping the other VCOs in line. He was often referred to as the ‘Indian Adjutant’.

Ashraf and Hexley in Birmingham, summer 1941

Ashraf was born in 1896 in Dubran, in what was then the North West Frontier Province of British India, now known as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Dubran was a remote place that remained beyond the reach of proper roads until the 1980s. To get there in the early twentieth century, he had to take a train to Haripur, sixty miles north of Rawalpindi. A tonga ride to Shah Maqsood town was the next stage, followed by a ten mile walk across the hills to Dubran village – a half-day in itself.

Dubran village

Ashraf was from the Karlal tribe of the Hazara people, speaking Hindko as his first language. His grandfather had served with the British under Major Abbott against the Sikh rulers of Punjab in the 1840s – Abbottabad is named after this officer.

Ashraf joined the RIASC as a sepoy at the age of 17 in 1913. Thereafter he rose steadily through the ranks. In the Great War he served in all the major campaigns that involved the Indian Army: in France, Egypt, Gallipoli and Mesopotamia.

By the time the Punjabis of Force K6 arrived in France in 1939, he had reached the highest VCO rank possible. He was a distinguished figure, with a fine-looking beard and moustache greying around the edges underneath his pagri, and a stern look in his eye. He was a man who commanded the respect of everyone he met, a soldier in his prime, with a lifetime of military experience.

Ashraf in London, May 1940

Over the next few months Ashraf was kept very busy, and covered a lot of kilometres. The units of Force K6 were spread over a wide area, some remaining at Marseilles, some proceeding to the BEF Line Of Communications HQ at Le Mans, while the 25th and 32nd companies were posted to work with the main Corps of the BEF in the north of France. As well as discipline, Ashraf’s role had an element of pastoral care to it – checking the morale of the men and liaising between Lt Col Hills, the force commander, and the VCOs on the ground, in command of a troop of 58 men, who knew what their men were experiencing.

Ashraf’s zooming around the countryside had its inevitable consequence on 17 February when the lorry he was in slid into a field in bad weather. Both Ashraf and the British RASC driver Pike were badly shaken but otherwise unhurt. According to a document in the National Archives, the concerned response by the British drivers showed the ‘esteem in which the Risaldar Major is held by British troops’. The bewhiskered VCO was winning friends and respect all round.

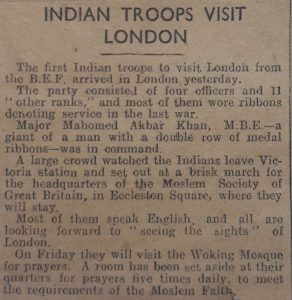

At the beginning of May, Ashraf was a member of a leave party that went to England. The party included Major Mohammed Akbar Khan and 13 hand-picked men from across Force K6. This was clearly a public relations exercise as much as anything else. Alongside their clear military purpose, Hills and the India Office were acutely aware that the soldiers of The Indian Contingent had a role as ambassadors for the Indian Army.

Force K6 leave party in London May 7th 1940, Buckingham Palace

The party were accommodated at the Moslem Society of Great Britain at 18 Ecclestone Square. The left France on Sunday 5 May, and arrived at Victoria station in the morning of Monday 6. The next day the Morning Advertiser reported:

Major Mahomed Akbar Khan, MBE – a giant of a man with a double row of medal ribbons – was in command.

A large crowd watched the Indians leave Victoria station and set out at a brisk march for the headquarters of the Moslem Society of Great Britain, in Ecclestone Square, where they will stay.

Most of them speak English, and all are looking forward to “seeing the sights” of London.

On Friday they will visit the Woking Mosque for prayers. A room has been set aside at their quarters for prayers five times daily, to meet the requirements of the Moslem Faith.

Morning Advertiser 7 May 1940

On Tuesday they went to the cinema, the India Office and Selfridge’s department store. They also visited Westminster Abbey and had a guided tour of the Houses of Parliament, hosted by Jocelyn Lucas, the MP for Portsmouth South. On Wednesday they visited the Fire Brigade and Harrods and attended a reception at the Overseas League. Thursday took them to the BBC, India House, the Royal Empire Society and a meeting with the Air Raid Precaution service. Friday is the day of communal prayer for Muslims, so Ashraf and his comrades went to Woking Mosque, the oldest purpose-built Mosque in the country. Several photos remain of that visit. But Friday was 10 May, the day of the German blitzkrieg in the west, and the day that Winston Churchill became Prime Minister. A momentous day for Britain and the world. Nevertheless Ashraf and the leave party finished its visit, going to Windsor Castle and Hampton Court, and returning to their units on 15 May. They had seen wartime London in all its glory, but returned to chaos in France.

Ashraf’s route out of France to escape the Germans was to be in the west, not via Dunkirk. The Headquarters found itself in Le Mans, and after a series of forced night-time marches, it arrived at St Nazaire. It was part of Operation Aerial, the lesser-known evacuation of the rest of the BEF via ports in the west of France. They left the port on 17 June, and arrived in Plymouth two days later. A full account of their hair-raising voyage can be found in chapter 4 of The Indian Contingent.

Ashraf in Ashbourne, Autumn 1940

On 8 August 8, the Indian Contingent was inspected at Ashbourne by King George VI. The Pathé newsreel cameras were present to capture the event. You can see Ashraf greeting the King on this film, at around 9mins 14 seconds.

A few weeks later, Hills recommended Ashraf for the Indian Order of Merit – the highest decoration that could be given in the Indian Army after the Victoria Cross. The citation refers to his ‘Outstanding devotion to duty’ and ‘Complete disregard of danger’. The award was confirmed on the first page of The London Gazette on 29th November.

One of Ashraf’s medals. Note that this is not the IOM

The ceremony to present the medal took place at Buckingham Palace on 25t February 1941. Ashraf was accompanied by Captain Lowman and Mrs Bell, a long-standing friend of the Indian Contingent. Ashraf wrote about the ceremony for the K6 newspaper, Wilayati Akhbar Haftawar:

When it was my turn to go to the king everyone was astonished that what I was going to do. My name was called out and took left turn and stepped forward and saluted. The king put the medal on my chest. He gave me a smile.

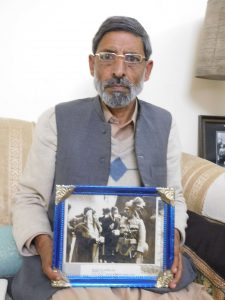

Ashraf was immensely proud of this achievement, but told people at the Palace that the credit was due to ‘the bravery, faithfulness and brilliance of my contingent’. This photo was one of his son’s most prized possessions.

Ashraf meets the King

As Force K6 became settled in the UK, Ashraf’s job was an important one. He continued to travel around the country, visiting all the units. including the three new companies that arrived in April 1941. He was photographed many times over, and appeared in numerous newspaper reports.

Ashraf with ZA Bokhari, London 1940

Ashraf stayed in the UK for several years – his precise date of departure is unclear. His date of return to India is also unclear, and he may have fought in Burma, as many of his K6 comrades did.

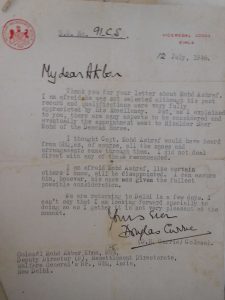

At the end of the war, Risaldar Major Ashraf had been in the British Indian Army for thirty-two years, and was an honorary captain. In 1946 he applied for the position of aide-de-camp to the viceroy Wavell. This was a position of great honour, and one fitting for a soldier with such a track record. However, the job went to another Risaldar, and a letter from Simla explains that ‘there are many aspects to be considered’ and realises that Ashraf ‘will be disappointed’. With thirty-three years’ service, with the Indian Order of Merit and having met the King at least twice, he was indeed disappointed at this outcome.

Letter from the Viceroy’s office

He retired soon after, and so never served in the army of the new state of Pakistan. Instead he settled down as a respectable country gentleman in his home village of Dubran. He married twice and had six children; he went on the Hajj in 1952, and he became a member of the local jirga or tribal council. He was also a moderately rich man – he employed several servants and had enough surplus funds to lend 2,000 rupees (worth around £150 in 1946) to a mine owner in Rangoon. He was even a friend of Ayub Khan, general and later president of Pakistan, who hailed from a village nearby.

Ashraf died in 1980 at the age of 84, and is buried in his home village of Dubran.

Ashraf’s grave in Dubran

In 1997, Queen Elizabeth came to visit Pakistan. Ashraf’s son Abdul Jalil took his mother, Ashraf ’s widow, and set off to Murree, aiming to meet the Queen. Abdul Jalil said, ‘we didn’t want anything – just recognition. We still have the old loyalties – a sense of Queen as symbolic figure.’ He hoped that his mother could meet her woman to woman, and he took along the prized photograph of Ashraf shaking hands with King George – two fathers together. The junior officials around the royal party would not listen, Abdul Jalil and his mother were unable even to get near the Queen and went away disappointed.

Ashraf’s son Abdul Jalil

Risaldar-Major Ashraf Khan was a loyalist of the old school, with 32 years service in the British Indian Army. He met the King-Emperor on more than occasion and had visited Buckingham Palace. The disappointment he felt in being turned down for the job of Wavell’s ADC lasted through his retirement and coloured the tone of my interview with his son. I got a strong sense of nostalgia for a vanished lifestyle, even betrayal. The 1997 snub from the monarch’s party was the culmination of that sense of disappointment. Fifty years earlier, a retired Risaldar-Major’s widow would have been held in high esteem and admitted to the royal presence, but sensitivities have changed. In the eyes of the world, the izzat-heavy identity of a retired Risaldar-Major in the British Indian Army no longer carries weight, and all that remains is a set of photographs and a few family memories.

At the new tea canteen with Mrs Lall, April 1941

Sources

The sources for this post include documents in the National Archives, the British Library and the Imperial War Museum, as well as my interview with Abdul Jalil on 13 March 2018. This interview took place at the house of the poet Omer Tarin, who also acted as translator and interpreter. I am also grateful to his assistant Zahid Akhtar for three of the photographs.